Gordian

Taking inspiration from The Witness, Braid, Tunic and many other great games, Gordian is a finely crafted puzzle game full of tricks and secrets.

The goal of the game is to help players learn about topology in a fun way by exploring the rule set Gordian uses to represent it.

This project was made for the 2022 Project Revival Jam 2 and received 1st place in the Reason category. It was also nominated for the Hobby, Game Jam and Student categories of GDWC 2022.

https://youtu.be/lFPFSGnLBj0

Puzzle Design

This game took on a lot of iterations before arriving at the current version. It started as a physics platformer in need of a knot tying system, only for me to realize that tying knots already had more than enough complexity for it’s own game.

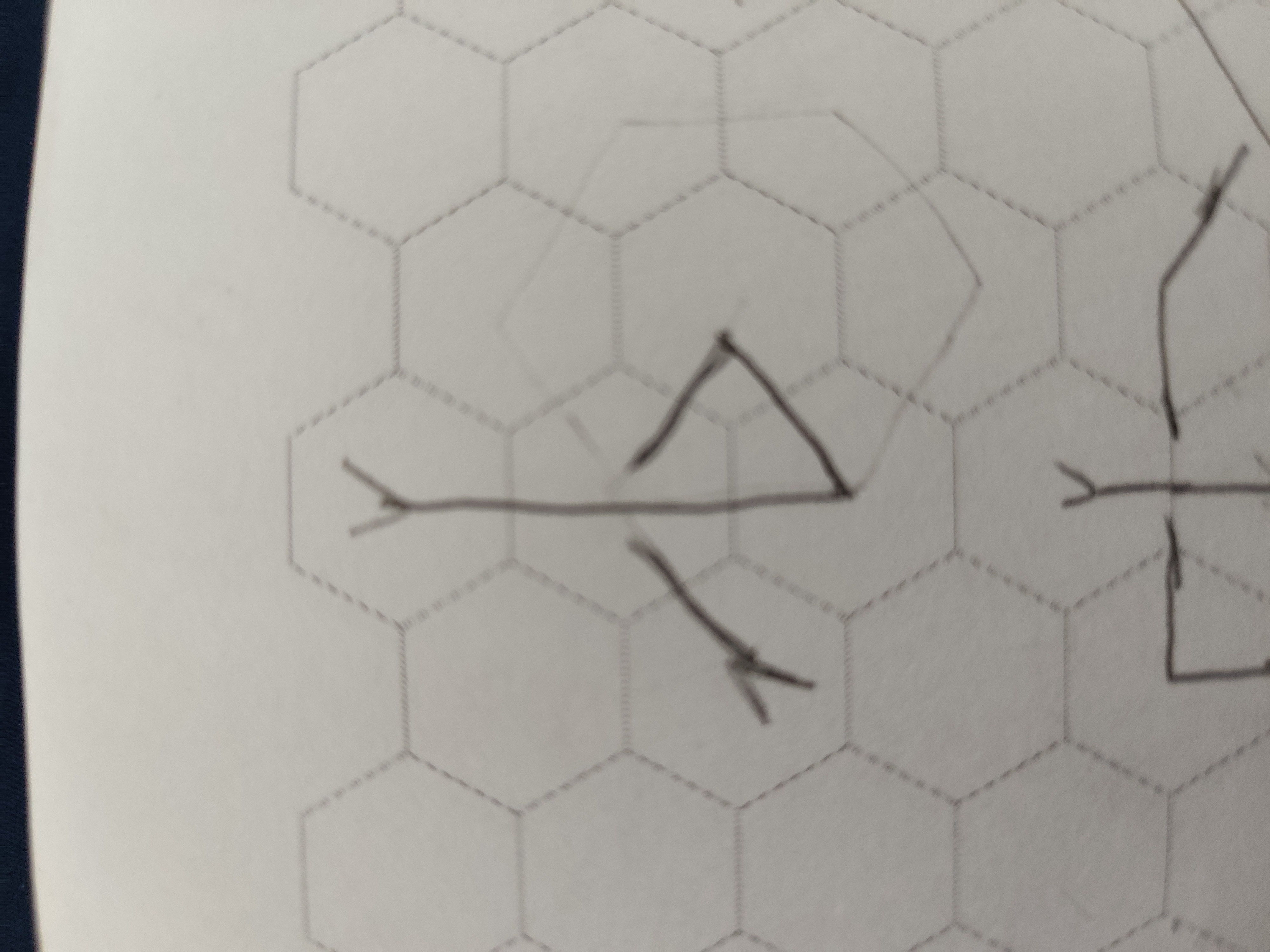

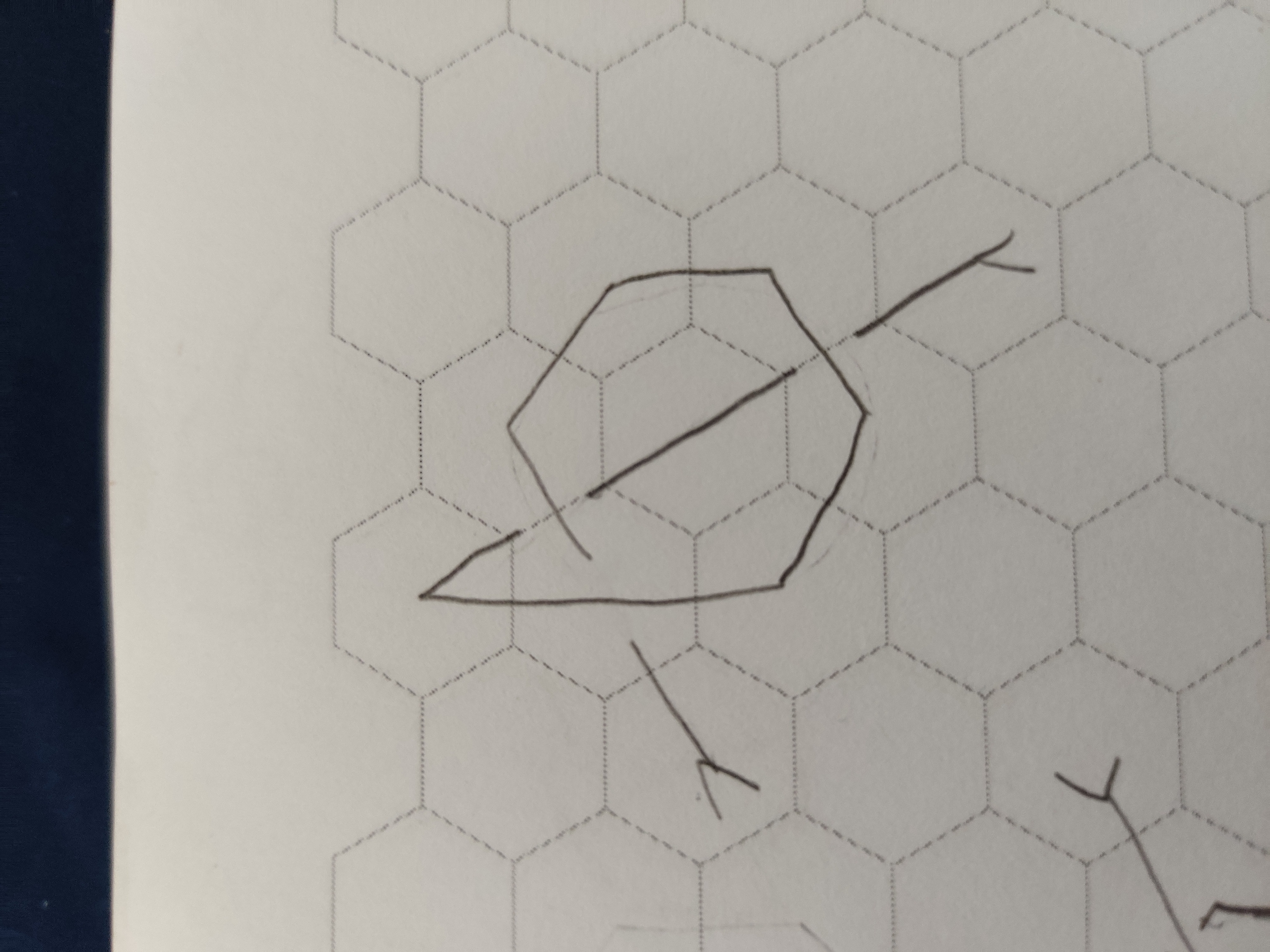

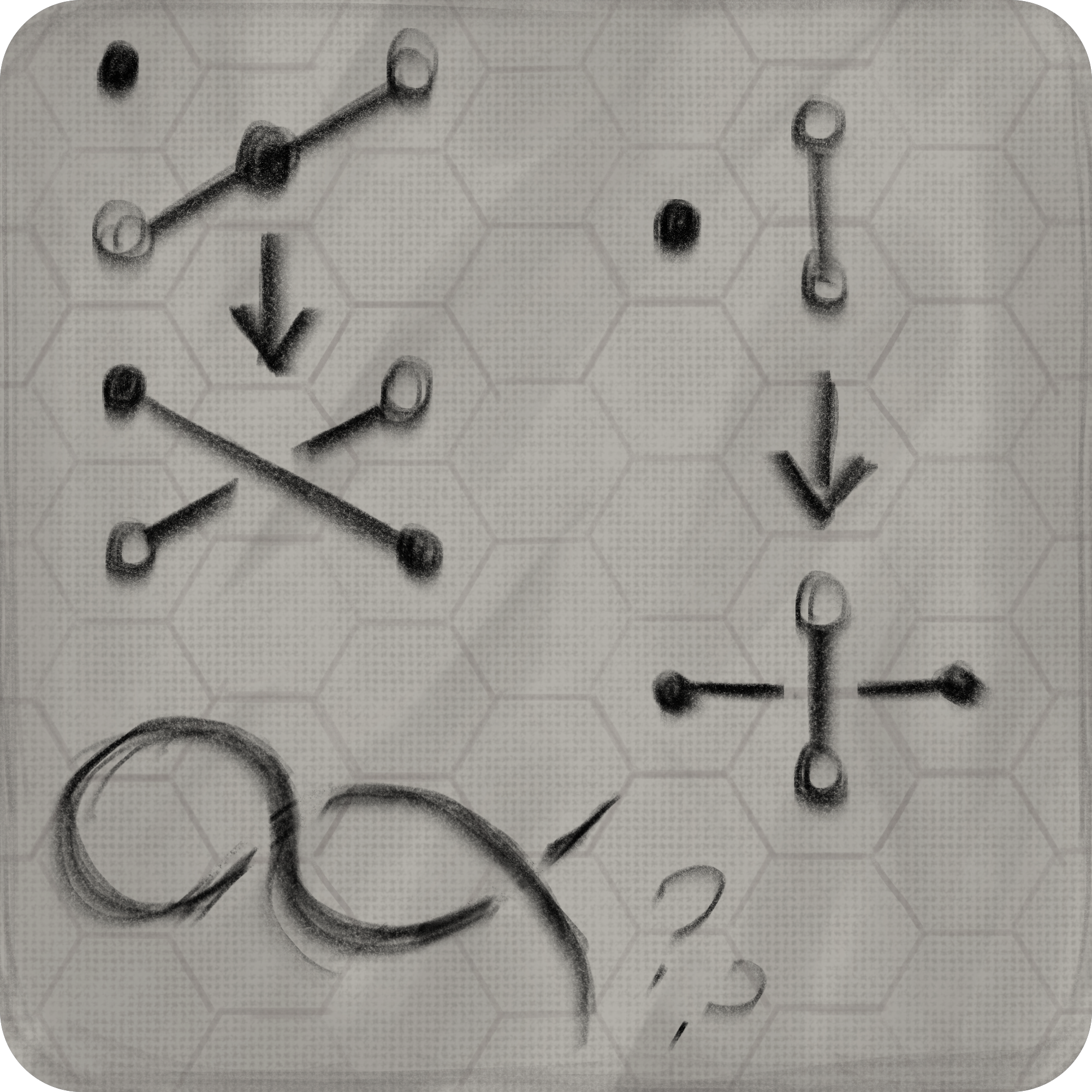

I came up with the current knot tying system by testing out several variations on organic chemistry graph paper, since it’s a bunch of hexagons. I took an idea from Magnum Opus, where you try to make the machines as small as possible. Me and my friend would often compete with each other to make it smaller and smaller, and the idea fit surprisingly well with Gordian.

I already knew plenty of knots, as I’ve spent a lot of time rock and tree climbing. When trying the knots I already knew, I found that I was constantly making new discoveries about the system.

When tying an overhand, I learned that you always need to leave a space when you need to go over and then under, and when tying the bowline, I realized that tying it from the other end made much smaller sizes possible.

But finding knots from the real world and just chucking them into a game isn’t all that interesting on it’s own. In order to make a solid puzzle game experience I needed two things: curation and progression.

Curation is the selection of good or interesting puzzles. Only about half of the puzzles in Gordian are taken directly from real world knots, the rest are created specifically to show off interesting mechanics of the Gordian puzzle space.

Progression is the order and manner in which the player accesses new puzzles. It’s important not just to put the easier puzzles earlier, but also to make sure there are enough early puzzles to teach the mechanical knowledge needed for later puzzles.

Curation was an iterative process. I would explore knots either in game or on paper. If I made an interesting discovery, I would then try to reduce the knot to a simpler form that still got across the same concept.

One of my favorite knots started out as a game breaking bug that happened on edge cases of the knot detection system. After making one small discovery I kept digging deeper into more and more interesting aspects of the puzzle space.

Progression was helped along by a lot of playtesting. I got pretty close to the order I wanted, but found that different people can have wildly different approaches to the same puzzle, so I often had to adjust leveling or add in an intermediary puzzle here or there to help players along.

Knot Theory

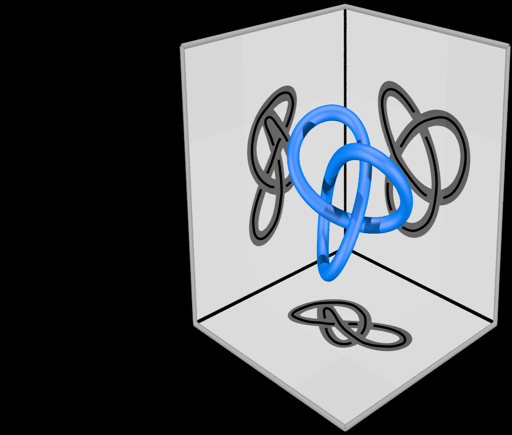

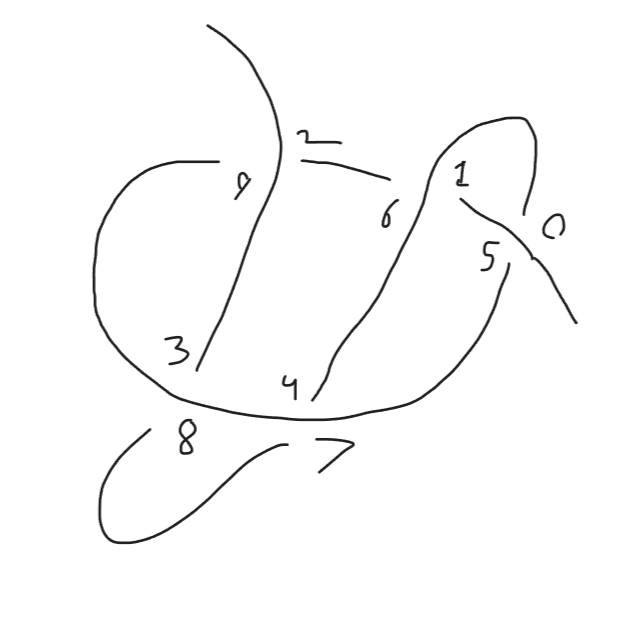

There were several programming challenges I faced when working on Gordian, but the first and most pressing issue was how to recognize knots. Obviously knots are 3 dimensional objects, but in the field of topology they commonly represent knots with 2 dimensional diagrams that show the positions of crosses over and under.

As with most programming challenges my first instinct was to do the brute force solution: track the overs and unders that the rope does and match them to a database of known knots. I quickly found some problems with this solution.

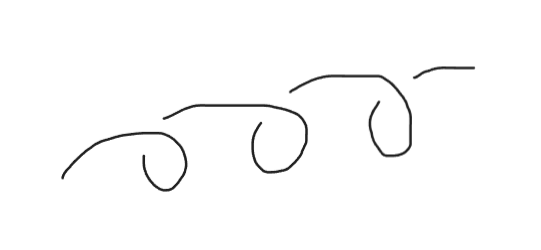

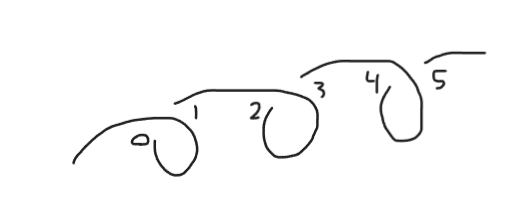

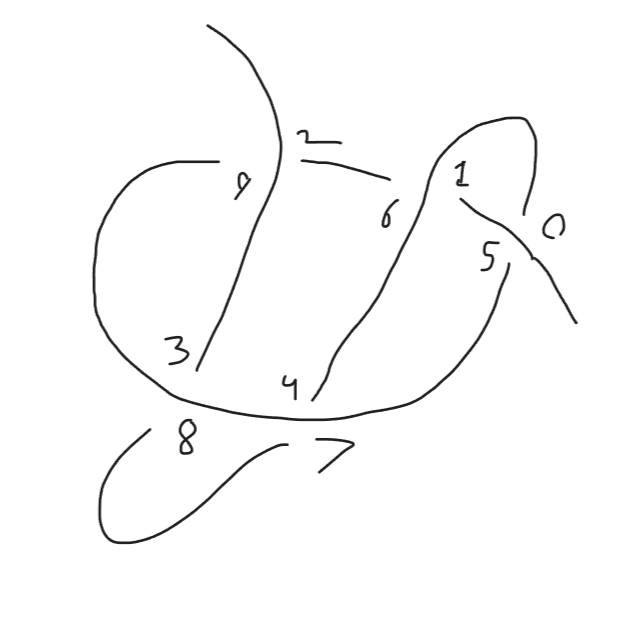

Take this overhand as an example; if you turned it into a series of overs and unders, you would get the following sequence: Over, Under, Over, Under, Over, Under.

Compare that to this series of twists, which should be considered a completely different knot: Over, Under, Over, Under, Over, Under.

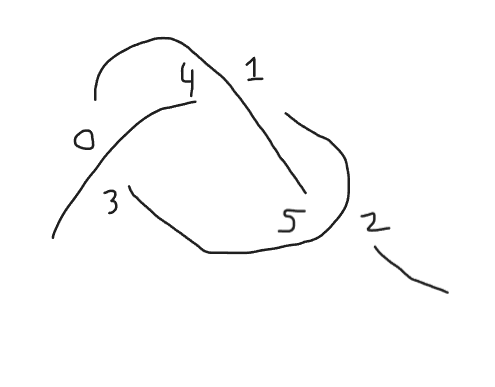

To fix this we can index the knot at each crossing, following from one end of the rope to the other. Then for each crossing we specify the other index that we crossed over. The overhand from before would now be written as: Over 3, Under 4, Over 5, Under 0, Over 1, Under 2.

And now the twists come out to: Over 1, Under 0, Over 3, Under 2, Over 5, Under 4.

So we solved one problem, but that’s not the end of our troubles. Now that we have a system that doesn’t see the wrong knot, we have to try to make sure it can see the right knot without having to input every variation by hand.

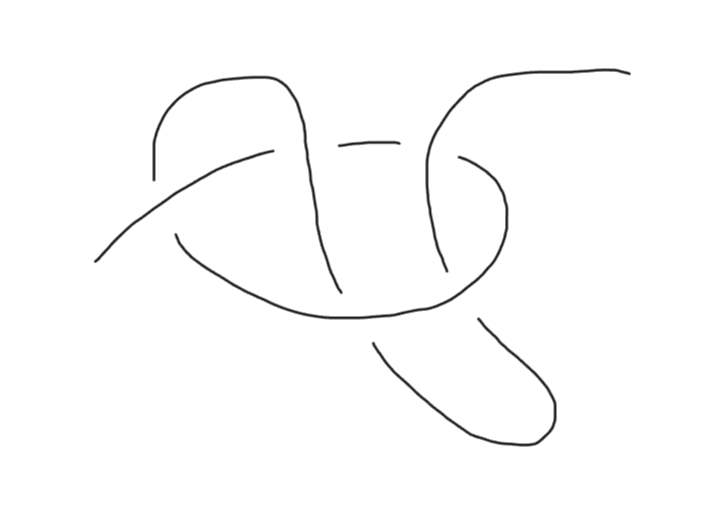

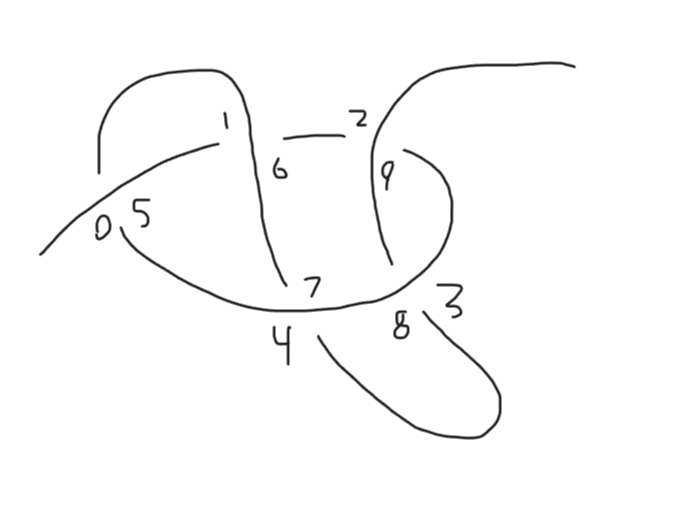

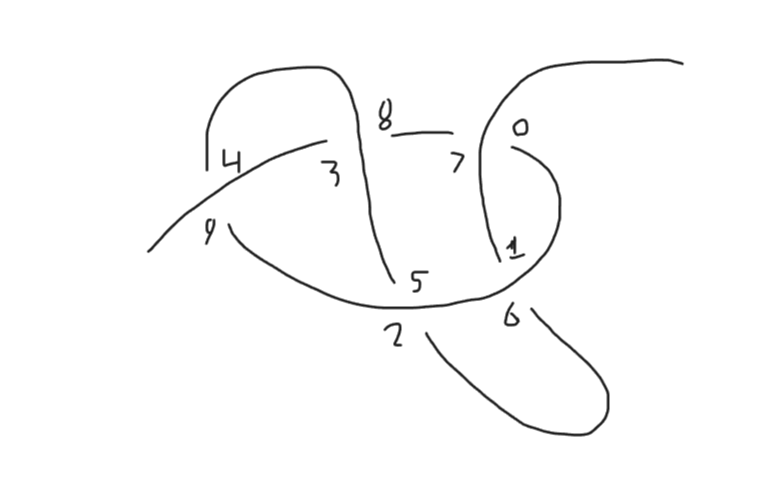

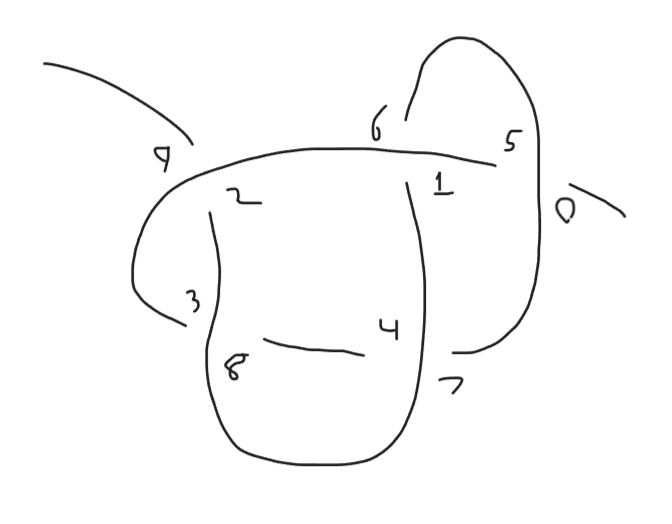

Let’s take a look at the slip knot as an example here: it’s quite similar to the overhand from before, but it’s a little less symmetrical.

When marked up it looks pretty good, but is there any other way to label it that should count as well?

How about we start from the other end of the rope and traverse backwards?

What if we took the mirror image of the knot?

What if we flipped the knot upside down without mirroring it?

What if we made all the overs unders and all the unders overs?

Each of these permutations look radically different. To put all of this in by hand would be a chore, and for some permutations we can stack them together, like flipping the knot and also starting from the other end. How could we reduce this to just one ideal representation of this knot?

To describe it mathematically: we have a series of parity problems that are combining to make our detection space combinatoric rather than linear.

When storing the knots, we need to get rid of this parity so that we can see knots that should be the same as the same.

Lets start with the problem of over unders becoming under overs. To solve this we simply store the knot as normal, and then ask what the first crossing is; over or under? We then enforce that the first move is always under, and flip the knot if needed.

Now we should take a look at the mirrored knot. Is it actually any different than our initial knot?

It looks different, but they both compute to: Over 5, Under 6, Under 9, Over 8, Over 7, Under 0, Over 1, Under 4, Under 3, Over 2. But what about the flipped knot?

As it turns out, the flipped knot is just the mirrored knot, with the overs and unders swapped, so this case is solved as well.

Finally, we have the starting end of the knot. There isn’t really a way to solve this with parity, as there’s nothing identifying about one end of a knot versus another.

Since we are only dealing with one rope, this can become a trade-off of computation versus data. I opted to save the bi-directionality for the checking step of the computation rather than storing backwards and forwards versions of all knots, which doubles the time it takes, but that’s just (2N), so it’s still in linear time.

To read more about this process, look at the write-up I did on the knot detection system here: MUNCK

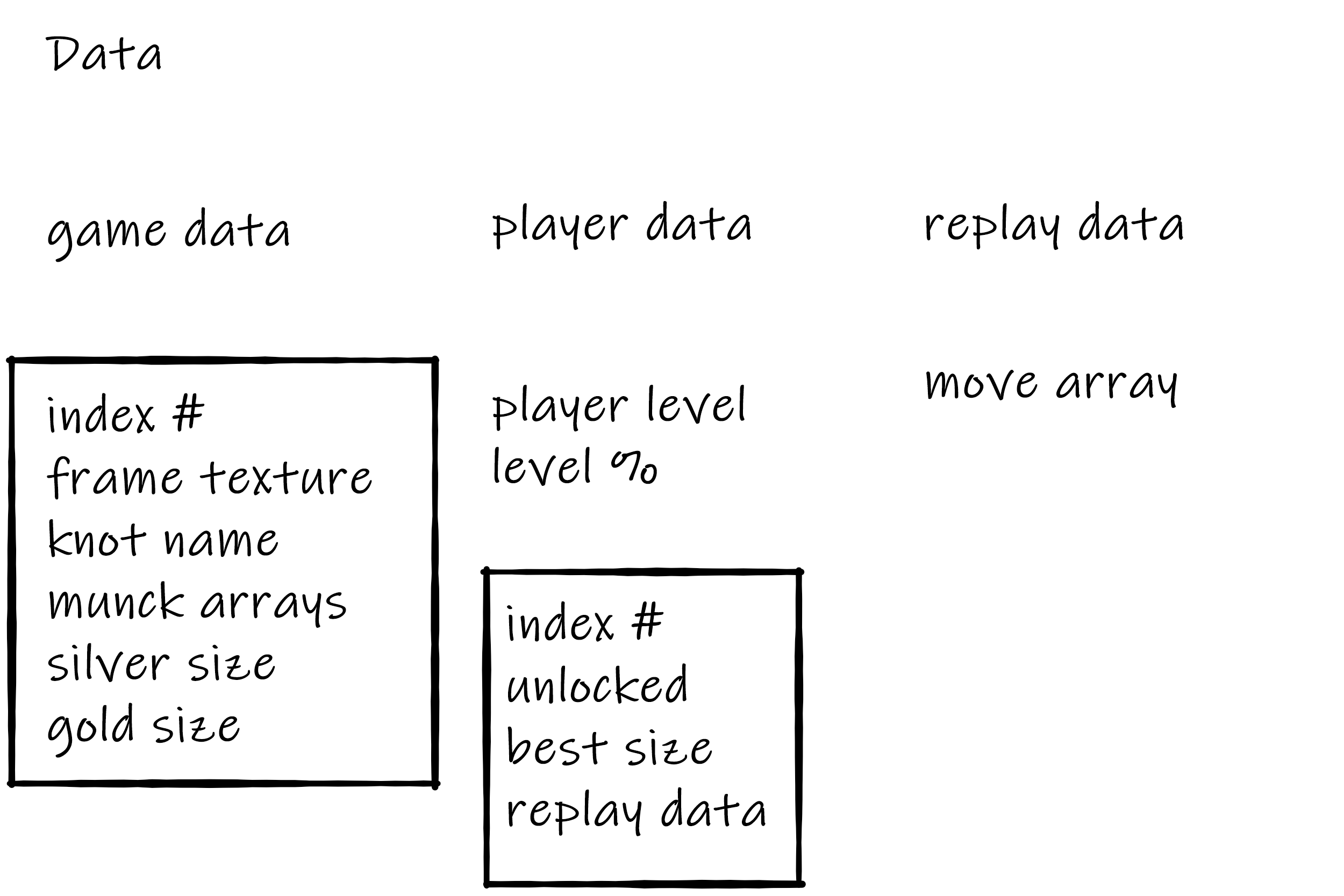

After dealing with knot detection, the next challenge I faced was saving this data in the game. Not only would I be saving the player’s progress, but I also wanted to make put all of the knot data in once place so I could change it there and have those changes propagate across the entire game. Below is a diagram describing my data storage design.

Sound Design

Sound is probably the first thing you notice when you open a game, and I wanted to make sure the sound design was as polished and unobtrusive as possible to make sure players are willing to spend time and effort exploring my systems.

The music layers ocean sounds, strings, and synth bells that remind me of Blade Runner. It also has a unique feature where it plays backwards when the player undoes their moves.

/assets/audio/gordian/gordian.wav

The backwards effect was achieved by having two versions of the main song, one forwards and one backwards, and playing the backwards version at a point in the song corresponding to the current position in the forwards version. I also added a bit of buffer to prevent the music from freezing.

/assets/audio/gordian/gordian-reversed.wav

Another thing I noticed in designing the music was that the strings and ocean sounds didn’t sound all that different reversed. Since the bells are used sparingly, you won’t really notice the effect until a ways into the game. It’s this kind of subtlety that games like this need, in order to turn the volume down on everything non-essential.

For the sound design of in-game actions like placing rope and tying knots, I wanted each sound to be distinct and to layer well when multiple actions happen at once. To achieve this, I used a combination of 2-3 sound files for each sound, randomly selecting and pitch-shifting them.

The sound of placing rope, for example, consists of a simple blip with pitch variation on each placement.

/assets/audio/gordian/place.wav

The undo sound is simply the placement sound played in reverse and with the volume lowered a bit.

/assets/audio/gordian/undo.wav

When you tie a legitimate knot, a rope drag sound plays. Since you can only tie knots after placing, it needed to sit well with the placement sound.

/assets/audio/gordian/tie.wav

If a new or smaller knot is tied, a tightening rope sound is layered on top of the placement and tie sounds.

/assets/audio/gordian/tighten.wav

Finally, if a player levels up because of a knot they tied, they’ll hear chimes that remind me of ship bells.

/assets/audio/gordian/level.wav

UX Design

When starting work on the game, I wanted to bring the art in pretty late in the process. Because of the design of the puzzles, I had to have a very clear idea of what I needed before the first puzzle frame was drawn.

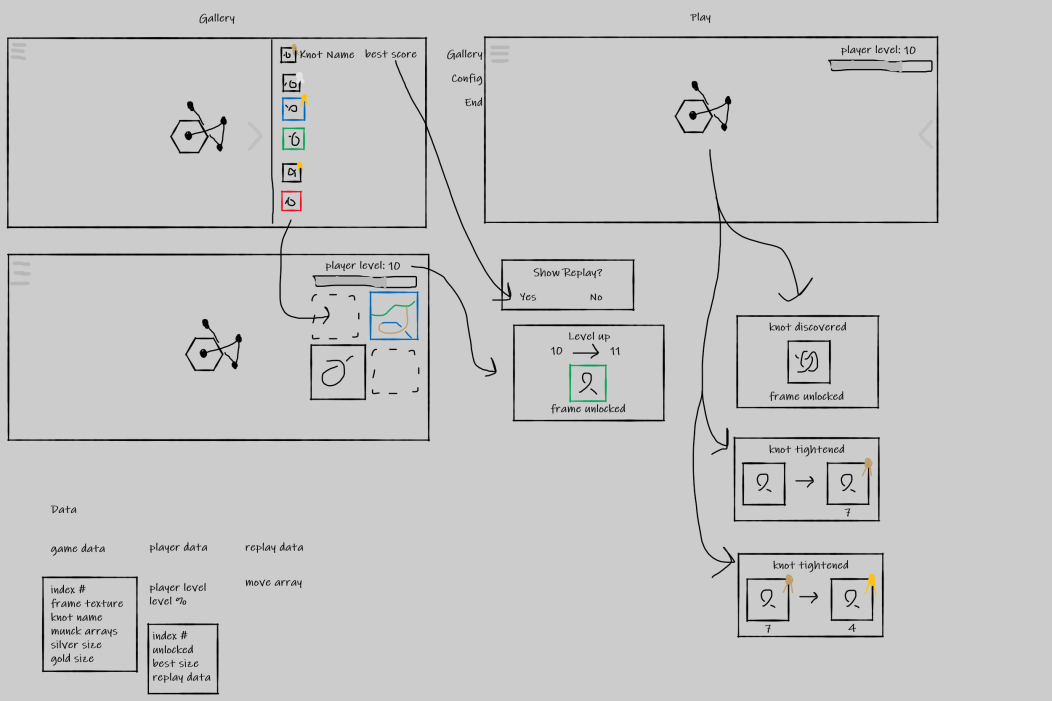

I started the process with UI Diagrams, showing how the game would work in as much detail as possible.

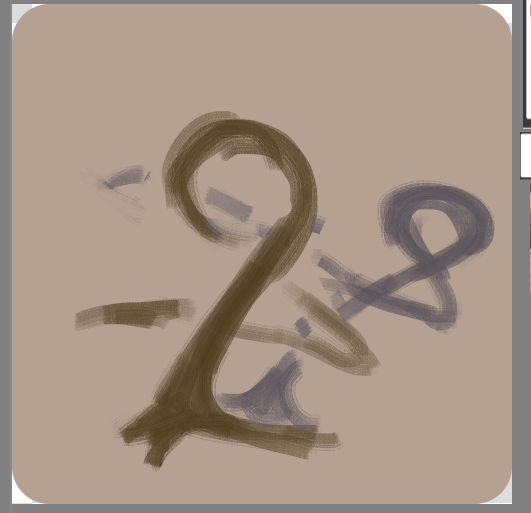

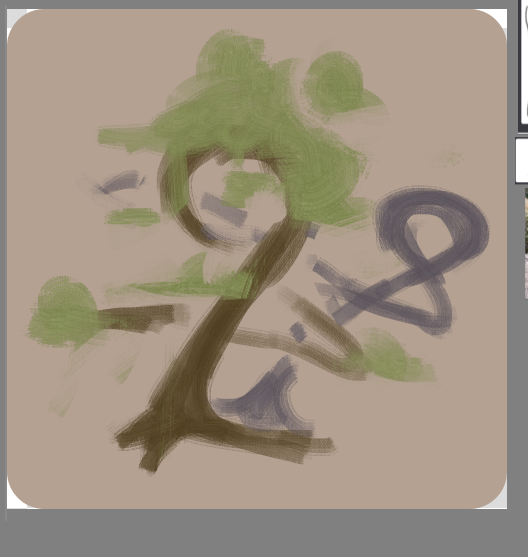

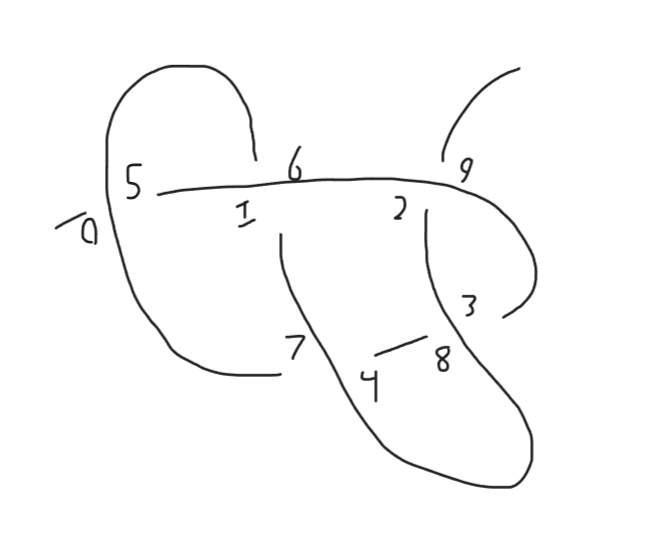

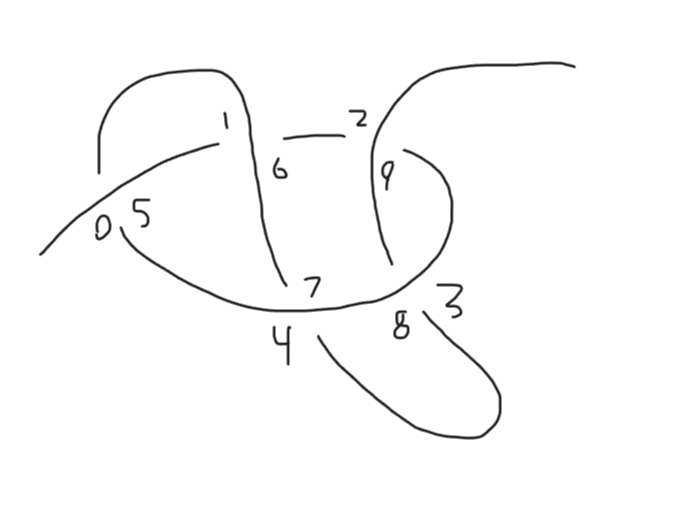

After making these diagrams, the next step was to put them in, programmer art and all. My first iteration of knot diagrams were simple but still conveyed the essential information - enough for me to get a lot of good playtesting, so I could add or remove knots as needed.

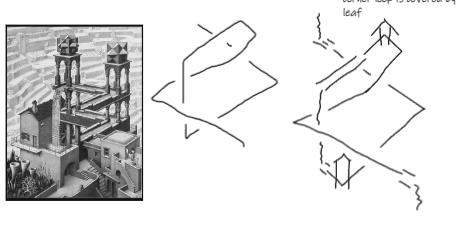

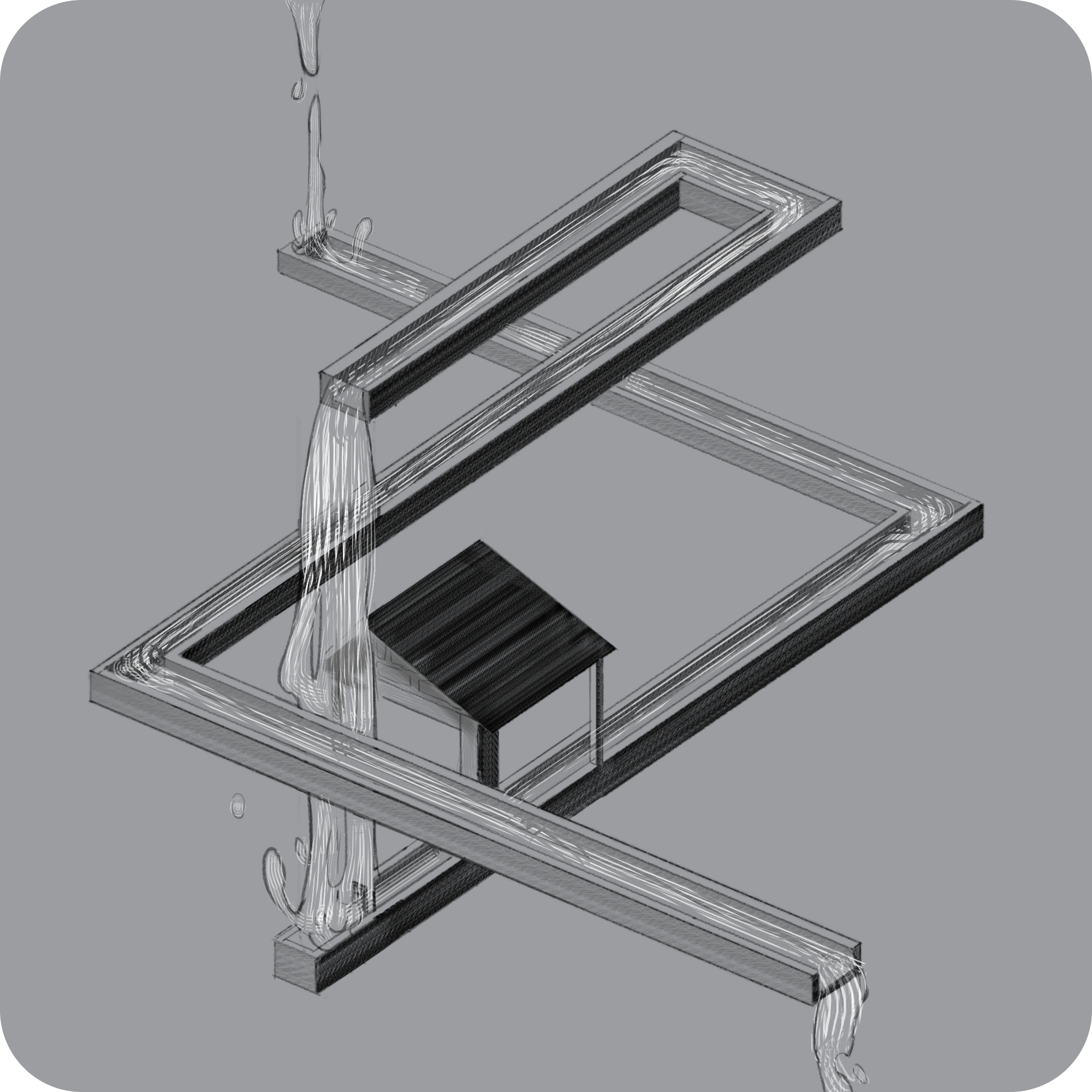

Once I was pretty confident in my design, I worked with an artist to iterate each knot and make sure it had all of the required information while also fitting in with the game’s themes. For each and every knot, we had to go back and forth several times to fine tune the discoverability of all the secrets. Below is the evolution of several knot designs:

These are the standard knots, they just need to clearly show the overs and unders for the player to replicate. We found that having too many horizontal lines was bad for UX, since the hexagon grid couldn’t replicate those horizontal lines.

This is the first tutorial knot. It takes heavy inspiration from Tunic’s tutorial pages, but also a little from my own use of chemistry graph paper.

The design for the waterfall was inspired by MC Escher. The first iteration of the final asset had an incorrect crossing. It can be quite difficult to keep track of that when also trying to make a good looking image.

Shadow was a hard one to get right, as players need to make a few intuitive leaps. This puzzle was based on similar ones found in The Witness and Taiji. I think the artist knocked it out of the park with this one.